Men of Faith

On January 16, 2017 by Mona AbouissaExploring the thread linking men rooted in religion, political ideology and the military, done in an experimental format.

Published in Mada Masr (Egypt) 2017

“Let the angels mark your ballot papers, they said!” Sobhy Saleh shouted to the crowd below him, motionless like leaves before a hurricane. “And the angels did!” The crowd roared. There were hundreds in the square in the busy Alexandrian neighborhood, mostly from low-income areas where faith was as popular as high cholesterol. They believed that angels did collaborate with the Muslim Brothers in those winter days of 2011 and brought Sobhy into the new parliament. In the 2005 elections, the policemen who laughed saying the Brothers would need divine intervention to win, little did they know back then what they did today, said Sobhy.

Sobhy was arrested before, but during the 2011 uprising he did not bother to pack, he knew it would be different this time. He was released and former president Hosni Mubarak was sent to jail. “We told them not to play with fire! He who plays with fire burns! So the earth shattered beneath them and now they are in jail!” Sobhy was invincible on the stage under florescent lights and camera flashes.

Holy wars throughout history were built on moments like this, and after 80 years underground, the Brothers won theirs. That winter, their party, Freedom and Justice, emerged as the most organised and grass-rooted organisation in the non-NDP political playground, and swiped 42 percent of seats in the lower house of Parliament.

The people around me were after salvation from hardships of their own. An elderly woman fainted beside me; she just won an Umrah trip. She got up, grabbed her galabeya, crawled over supporters and banners like an octopus reaching out with her arms to hug and kiss Sobhy. A boy urged me to write his name on a piece of paper for a raffle of electric-hoovers, juice-makers, irons and more. He did not win. A girl on the other side, trembling, asked me to write a job request to Sobhy. A mother was invited to climb on stage and held a poster of her 16 year-old son, he had recently died in clashes that were too frequent after the collapse of Mubarak’s state. If the elections were annulled by the Supreme Council of Armed Forces that took charge of the leaderless country since the 2011 revolution, the Brothers warned they and their followers would storm the streets. A man started to shout into a loudspeaker, “God is great and praise be to Him, one of us is in parliament!” From small to big, young to old, the crowd chanted back, “God is great and praise be to Him, one of us is in parliament!”

I am no stranger to vocation. In 1990s Moscow, there were two choices for the offspring of Soviet-Arab comradeships like myself whose fathers decided on Arabic education over Russian. There were two choices; Iraqi or Saudi school. I went to both. At the Saudi School, the teachers of our five religious subjects (Tawheed, Jurisprudence, Hadith, Qura’an and its exegesis) made sure that our soft teenage brains considered, even feared, the divine watching over our deeds. Wahhabi education offered religious wealth and left no room for interpretation or questioning. There was a year when I spent mornings in prayer. I abstained from music, just as Titanic’s romantic single made a whole teenage generation of post-Soviets walk on clouds, wearing t-shirts with Rose and Jack. Listening to devilish instruments was a fisq (obscenity) punishable by pouring hot lead into listeners ears. From my Wahhabi schooling I understood something – faith leaves an imprint. I can still remember how it felt; being blessed, inspired, singled-out by a sense of purpose. A piece of it never left me. Then after the 2011 revolution, Egypt experienced a surge of faith. Everything, for the first time in 30 years, was possible. I guess that is what lead me to a square where angels were at work.

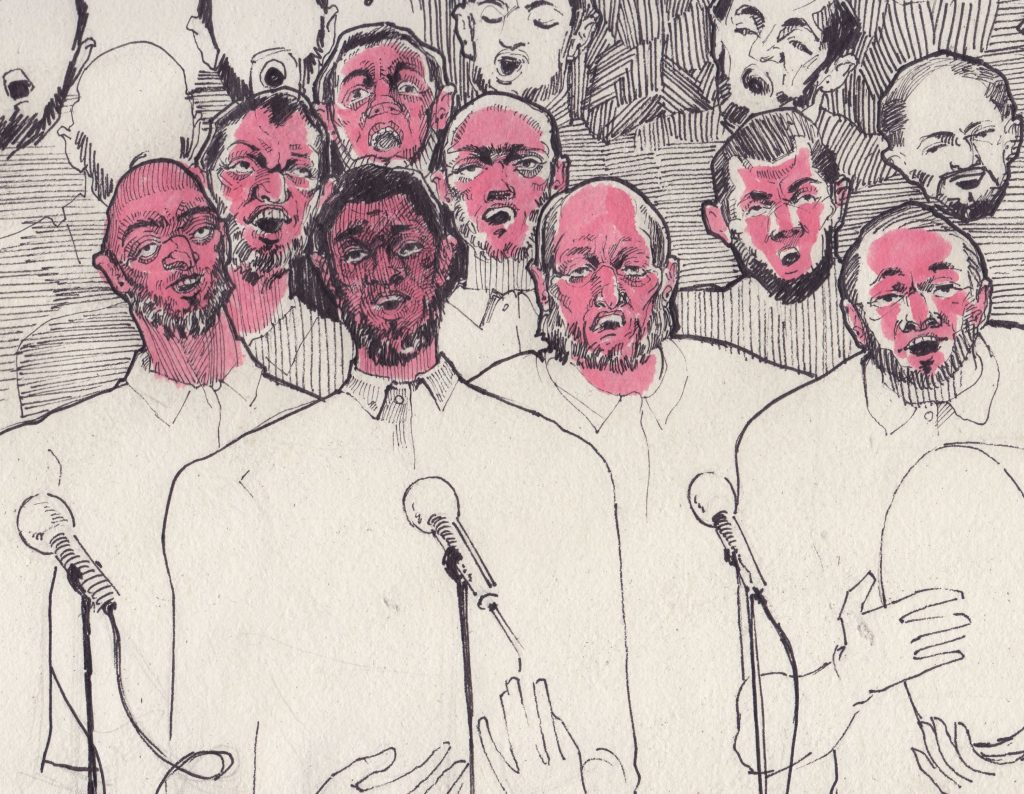

Young clean-shaven men climbed on stage and started to sing. The Freedom and Justice candidates waved holding their hands. The crowd sang along, “Oh the white moon rose over us, from the valley of Wada, and we owe it to show gratefulness, where the call is Allah.” This choir was condemned by the Brotherhood’s shura council when it started in 1989, for the very same dilemma about music I had had. Music is a debatable issue in Islam, depending on the doctrine (Wahhabi, Sunni, etc), there are rules for what kind of instruments are allowed, what message should be conveyed and what human emotions should not be provoked. It’s a thin line between halal and haram, and young choristers like Mohamed Saeed walked it. “We were Brothers and we liked singing, what we could do with this?” The first generation of the brotherhood choristers did not give up then, it took decades for them to negotiate and put together a shura-approved halal repertoire (no love triumphs, no corporal desires, and never dancing) devoted to Islamic principles and Brotherhood conquests. Saeed was one of the first Brotherhood choristers, he attended a music school and joined the choir in the eighties. “Bit by bit, first there was no musical instruments, later we added drums, and then flutes and synthesizer,” Saeed said. Now he was the manager of the fourth and most famous incarnation of the choir formed after the revolution, “Shat Eskanderia”.

Before the revolution, under Mubarak’s emergency law, the choirs performed against politics. The young choristers were arrested at home in front of their parents like criminals or terrorists. They were interrogated about what exactly they did, why they did it, who sponsored them, and whether they grew beards. Before the 2011 revolution, the choristers usually performed in secrecy for the Brotherhood’s special occasions. Still, the roads to their concerts were patrolled, areas shut down, audiences searched and concerts filmed. The flat where the choir rehearsed was in spitting distance of the secret police building. “So they do not waste time looking for us,” Saeed laughed. The choristers traveled separately undercover while their instruments made their own way on a train to the venues. It was raw belief that kept them going, that they put across the message. They learned to survive. “If you are afraid then you should not be a member of the Brotherhood,” Saeed smirked.

Islam Talaat was an alto soloist. He knew the Quran by heart from the age of eight, sang to the moon, and kept online female fans at bay. He had “God’s gift”, as the choristers were eventually categorized, that sometimes made the Brothers shed a tear. He said if it were not for them, he would not be a singer. Talaat was planning to release his own video clip after winning the Brotherhood singing competition. To prove it, he trilled a song about the prophet, closing his eyes and released a long vocal stream in the coffee shop where we sat, “that is the rhythm of sadness,” he said. His favorite.

Diaa Al-Din was not as sentimental as Talaat. He was born into a Salafi family. Unsatisfied by their archaic division of sheikhs and followers, he joined the Muslim Brothers. He passed a four year-trial and became a member tasked with monitoring newcomers. It had been nine years with the Brothers and Diaa Al-Din enjoyed being part of a system. He often used “we” rather than ‘I’. He sat behind a big desk, I sat on a visitor’s chair – one of those two chairs that are preferably lower than the host’s chair, positioned opposite. They make you look over your shoulder when addressing the host. The purpose of this common official geometry always eluded me, unless it was to make the guest slightly uncomfortable. I asked him why he sings? He replied that Egypt suffered from being liberal; the previous regime supported vulgar pop-music and now they, the Brothers, had a chance to reform the culture. And Diaa al-Din was at the center of it. However, his Salafi family would not come to see him sing.

Things changed for the Brothers in the following two years. “Come visit us, we are like your sisters,” said a Brother on the phone two years later. He told me he was responsible for media at the organization. Their reign was about to collapse. Fixated on political control rather than addressing the country’s economic and social problems, the Brothers were losing ministers, the public and, more importantly, the army’s support. Probably they needed some positive publicity and I was one of their last resorts. “I am flattered,” I replied. This was the last I heard from them. Soon after the phone call, people took the streets urging the Brotherhood-bred president Mohamed Morsi to step down. The military ordered the arrest of Morsi, along with the invincible Sobhy and over 100 Brotherhood MPs. The Brothers and their followers revolted and violence escalated, around 1400 people were killed in the process (Sobhy’s premonition). When the Brothers became hunted terrorists, I tried to reach the choir boys but in vain. I am left wondering if Talaat ever managed to release his own video clip.

One day, 10-year-old Essam Shaaban started a demonstration in Assiut. He was playing with his friends when a storm rumbled far way. Shaaban, like any young man in 1990s Upper Egypt, grew up surrounded by political Islamist factions. He usually hung out with people older than him, his uncles were Islamist leaders, so his friends thought he knew best. “Essam, where does thunder come from?” In a theatrical manner, he declared, “Thunder comes from the wrath of God!” and they shouted after him “thunder comes from the wrath of God!” They picked Shaaban up on their shoulders and moved into the streets chanting after him, “Thunder comes from wrath of God!” Shaaban looked behind him and could not find the end of his chanting crowd. A child’s game turned into a demonstration which became the talk of the village. This event would affect his life, the “weird feeling” he had in a demonstration “that you say to the world you exist and you are able to explain this world and to change it, you have power and echo,” he said. In his future demonstrations, he would always look for that feeling.

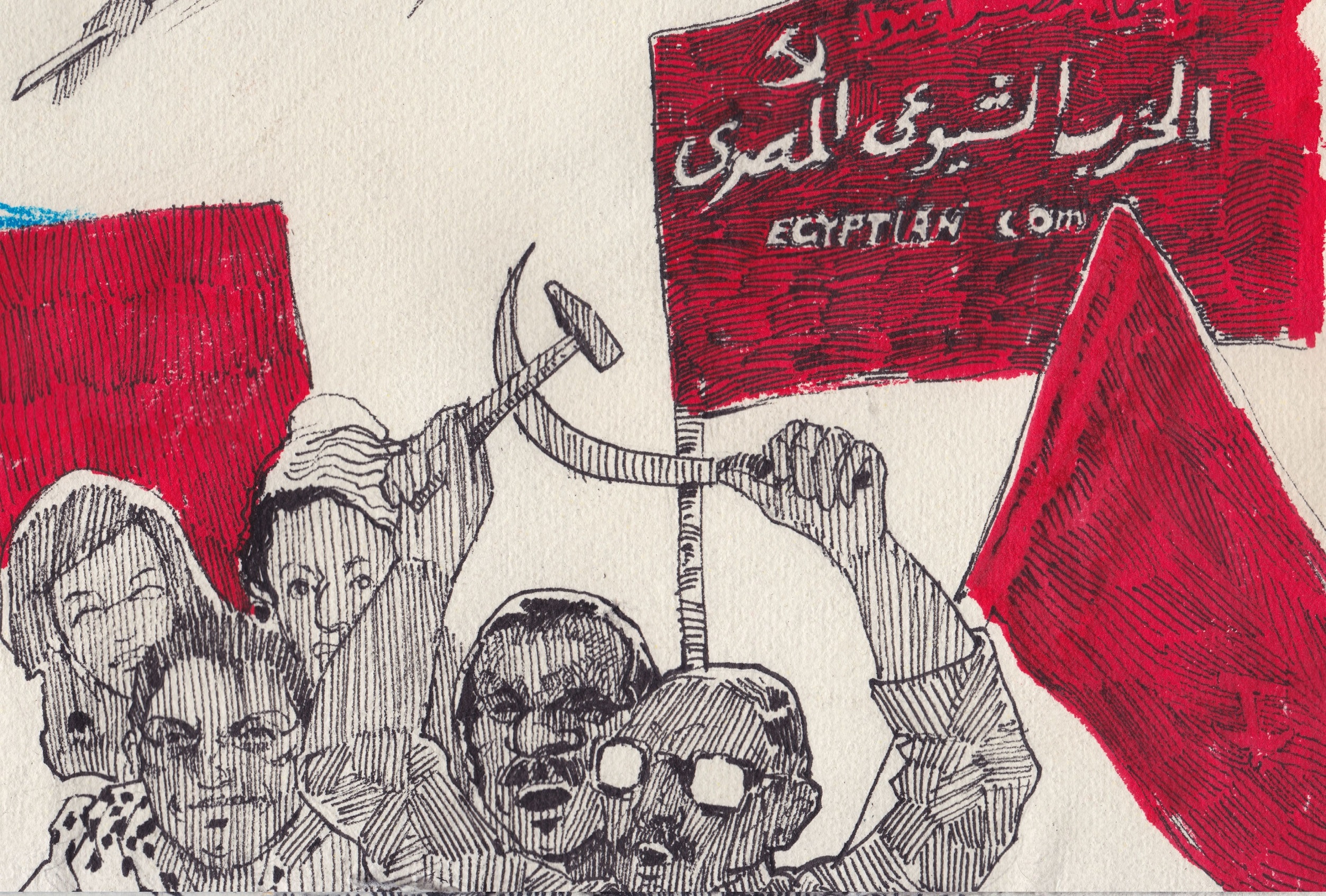

“Communist till death!” the men shouted, waving red flags. Sweat ran down their necks and capillaries pulsated on their faces. It was May Day 2014 and the army had grown popular since the 2013 uprising against the Brothers. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, an army-backed candidate who played a key role in ousting his predecessor Morsi, was leading in the upcoming presidential elections. The public need for military-tested security and the weak opposition was in his favor. The communists took no mercy on their vocal cords. Shaaban was among them, but he was not shouting, not like back in 2013 when they protested against the Muslim Brothers government just two months prior President Morsi’s arrest. Shaaban shouted with the rest they would never “kiss the morshed’s feet!” That was a bigger and louder demonstration, traffic paralysed, passerbys mesmerized, and TV vans avid for any action when this red force of nature faced a black police cordon.

That 2013 demonstration was my first with the communists. I also waved a red flag like them. It reminded me of Soviet military parades from my childhood. We were superstars in the heart of Cairo back then, now we were a fraction of it; just a few young Trotskyists from the Revolutionary Socialists and the Egyptian Communist Party. Another three leftist parties from the newly-formed Coalition of Socialist Forces were absent, although Salah Adly, the Communist Party secretary, had invited them. That upset him.

Shaaban met Adly when he left his Islamist enclave and moved to Cairo in the early 2000s. He was never meant to be an Islamist; it was just a beginning in his crusade against corruption and injustice. He read Karl Marx, about socialism, Nasserism and even alternative Islamic thought and he found there was a completely different world from his. Shaaban met leftist intellectuals who spent their 20s in Nasser’s prisons and recruited his peers into socialist struggle. Today, however, Shaaban was troubled. Just a few weeks prior, he started a fight at the Communist Party’s headquarters when the comrades decided the party’s stance at the elections. Shaaban supported the civilian politician Hamdeen Sabbahi, as many young members did, while the older comrades preferred the security promised by Sisi. That day, the old and young reared, pushing chairs over, swinging fists and grabbing each other’s shirts, spitting out accusations of Islamist treachery and military infiltrators. Adly shouted at them to stop. Shaaban disappeared to the kitchen to smoke away the tension.

Under the statue of Talaat Harb, a reformist who long ago tried to fix Egypt, I approached Shaaban and asked why they keep doing it. “So people know we exist.”

The chants switched from socialist agenda to “down with the military regime!” To that Adly and his comrades frowned and we all aimed for a seedy pub to get drunk. After all, it was the Party’s anniversary. It was officially announced by Adly’s mentors in prison back in 1975 after president Anwar Sadat rounded up 500 leftists for inciting a workers strike. At the time, usually in prisons was when the communists could finally all get together. Outside they only could meet in small groups. They were hunted state saboteurs until the collapse of the National Democratic Party monopoly in April 2011, their communist party, amongst many other parties, became legal. They didn’t have to camouflage their headquarters, use code names and keep secret hideouts. They had a website with Adly’s number on it. And there would be no longer policemen outside this pub tasked with monitoring them.

“For Marx!” we downed our Stellas “For Marx!” Adly and his cheerful drunk peers were born into Nasser’s nationalism. They wanted to fix social inequality, where the rich used the poor. Marx and Lenin changed their lives. They joined underground leftist cells. Young Adly was sweating over a Roneo keeping a low profile (meaning no protesting or meeting comrades or clashing with the Brothers at the university). Those bulky mimeographs had a mission of their own, to keep the network between elders, workers, farmers and young recruits like Adly running. He was not arrested in 1975 and printed out the Party’s declarations. Only in 1981 were Adly and his “partner in crime” arrested. After his release, following Sadat’s assassination, he had enough of the secret life and worked his way up the politburo.

At the pub, the communists longed for old times, the thrill of sabotage, the trips to the USSR, the power to stir streets. They know they are a pale version of the 80-year-old leftist movement (but giving up was not in their flag-red veins). Some say it is because President Hosni Mubarak “scraped” the political scene of any opposition. Others spoke of “the communist curse” which tormented Adly’s mentors back through the 1950s and 1960s, whose ideological disputes were infamous; their factions split like subatomic muons. What remained firm across generations of communists with their splits and curses and fights, theoretical or actual fist-to-comrade’s-face, what outlived their leaders, the Soviet Union and one day may outlive them, is a belief in socialist deliverance. “For Marx!” I raised my Stella.

Now it was Adly’s job to keep the party intact, protect the comrades from ideological absolutism and the imperfection of day-to-day politics. Not to repeat his mentors’ mistakes.

Shaaban left the Party claiming he could not support the Party’s political direction anymore, which conflicted with his Marxist beliefs. He said the 1970s, Adly’s generation, lost the socialist dream of their forefathers who sacrificed everything for it. It was not easy to leave the party that saw him grow. Shaaban shaved his moustache and is now working with steely feminists, some as old as the republic itself. I asked him if he still believed in communism. “Yes, I do believe in humanitarian Marxism. Biased towards people”

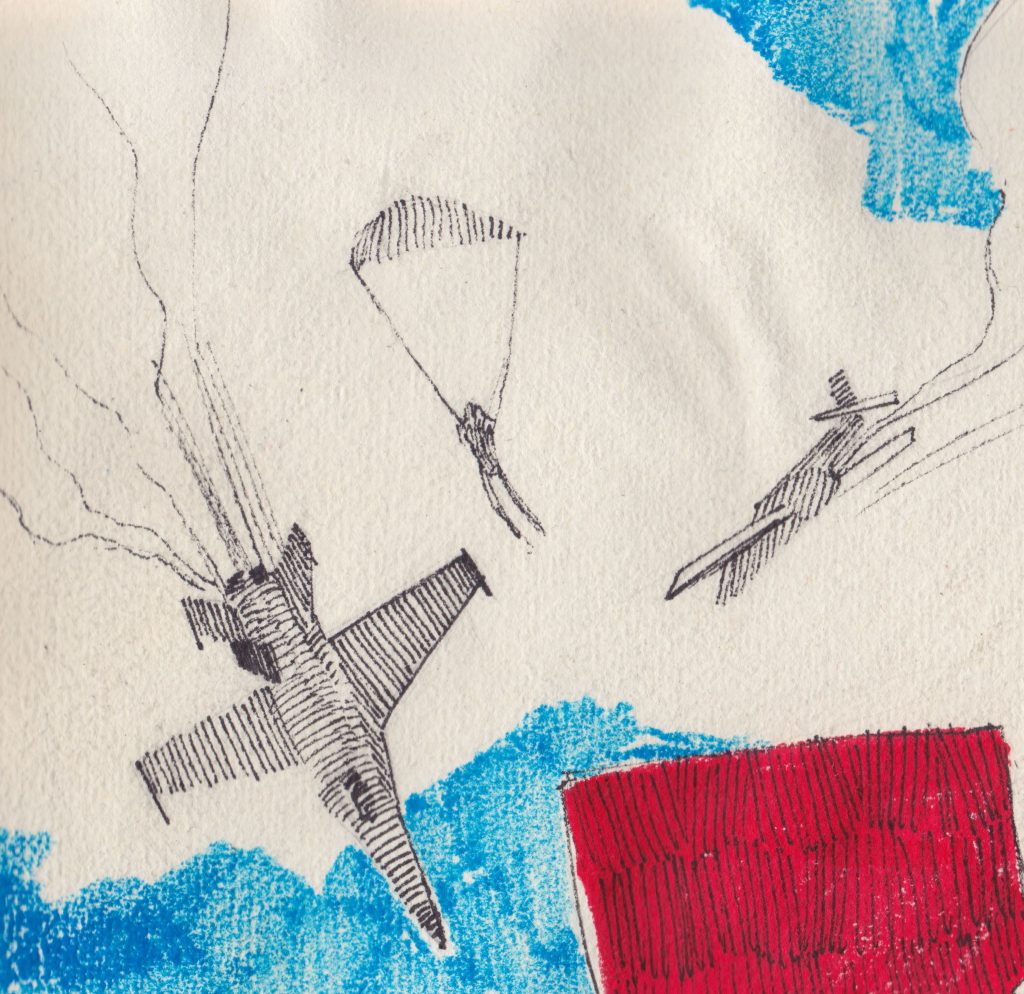

Mohamed Abu Bakr’s vocation was to break the sound barrier and to serve his country. “Two kinds of men result from leading the life of a war pilot; those who become bitter even aggressive, and those who crack jokes all the time,” said the aviator, “I am the joker. Ha-ha-ha.” Reining his MiG-21 chasing Israeli Phantoms across the sky was Abu Bakr’s second nature.

I can’t compare anything to the sharpness and mercilessness of the generals’ sense of humor, a defence mechanism crafted in warzones between 1969 to 1973 for a single purpose: to keep them sane. At their former battlefields in Sinai, they passed through their frenzied entourage who called them “supreme general” or “heroes of the nation” or “diamond shield that protects Egypt”. They were a state secret for 40 years, after 2013, their front expanded; unofficial think tanks that decoded “enemy” conspiracies, informal pro-army youth hubs preaching the “1973 spirit”, army-civilian events celebrating the achievements of army men. Men wanted to be them and women wanted to be with them. The generals brushed away the frenzy, “I am just a soldier, the real heroes died in the war”.

On stage I watched Abu Bakr and his earth-bound comrades speak of the patriotic fealty they swore; the Israelis they killed, the friends they watched die, the number of blown off limbs or shrapnel scars, and of every grain of Egyptian soil they defended with God on their side. The crowd was hungry for more dead enemies, more patriotic rhetoric and more evidence that those generals will defend the pride and dignity of Egypt just as they did in 1973. Their followers were born into Nasser’s nationalism, Sadat’s military triumphs and Mubarak’s three-decades of peace, and for them the security of an army bear-hug was better than a risky flirtation with democracy. For that very moment, those civilians held the fate of their homeland with the generals. They shouted “Long Live Egypt!” The generals remained cool.

“Egypt is in danger!” thundered aviator Abu Bakr at the audience who whipped out their camera phones. His nose is scared and his spine damaged after an unfortunate ejection during one of his dogfights. Abu Bakr said he got the “fear of thousand demons” upon hearing ejection, the pilots feared ejecting more than anything, they could be caught by Israelis or beaten up by locals or death in the process. Abu Bakr’s comrade was captured by Israelis, put in a box with a hole above his forehead for water to drip. He was later released but never recovered. Abu Bakr does not joke with him when they see each other, he can punch him for that. Abu Bakr was lucky, he landed breaking a leg on the Egyptian side and managed to convince angry peasants that he was not an Israeli pilot. From then on, he was bound to physiotherapy in military hospitals. Outside the generals’ front, everyone from Americans, anti-military democrats, terrorists, conspirators, paid agents, drug dealers destroying young folk, to the old Israeli foe, were plotting to destroy Egypt.

My Wahhabi education served me well with the Muslim Brothers, just as my communist background did when I toasted Karl Marx with Adly’s comrades. Yet the generals were tricky. Like any spawn of post-colonial trauma, I studied patriotism at school (Iraqi, Saudi and Egyptian) where the army, glorious and selfless, was a centrepiece. I could not fathom its purpose until 2013 when allies were separated from foes on the merit of this school subject. Now, among the generals and true patriots, I tried to remember the syllabus. Once in their space, the generals could be prone to invade, an old habit. General Tolba Radwan interrogated many Israelis during the War of Attrition and later during his service with military intelligence he stared down his countrymen. Once I found myself thrown into his psychological minefield under the stare of his shrapnel damaged eye (are you a KGB spy? Why do you want to know? Beware you are surrounded by generals. Ha-ha-ha), there were two tactics; submission or retaliation. I, personally, retaliated using my best defence: humor.

Abu Bakr’s generation of generals graduated into the shock of 1967, after Egypt’s defeat by the Israelis in six days. The masses belief in the republic’s invincibility collapsed. A 20-year-old Abu Bakr watched the airports torched as he drove to engage. He wondered if there would be there anything left. Egypt lost most of its air force. People protested, blaming pilots. Young comrade Adly was one of them. Abu Bakr did not wear his uniform in public. Vengeance was what he wanted. Many officers like him sought revenge and were ready to give their lives to defend Egypt’s honor. Nasser pushed reluctant Soviet allies for more MiGs. After two years, he was swirling and leaving sonic booms over occupied Sinai in one of the last aerial dogfights in history.

“Mostly pilots want to forget,” Abu Bakr told me in a rare instance of candor. When he was in a cockpit, switched on his afterburners, he thought nothing of fear; he locked himself away focusing only on a target. He would return to base finding the unfinished lunch of his mate who had plunged his MiG into an Israeli outpost, still warm. They laughed as if everything was fine. Only in a moment of privacy with a cup of coffee, could one quietly collapse. General Abu Bakr liked to speak of the dogfights, martyrs, that 1967 was not the pilots’ fault, and of his post-war occupation flying presidents on state visits – he was called the presidents’ pilot.

But there was a dark side tucked away from armyphiliac followers, he was not alone. Another supersonic general, Ahmed Mansoury, in public, was the most swashbuckling with his red leather jacket and his flying record (he crash-landed on a highway heading towards a speeding truck after a tough dogfight with eight Phantoms). But in the privacy of his chambers, under his collages of press clippings and photos of him with his MiG, his medals and certificates from presidents, he was alone, sleeping in a coffin-sized bed. “I am preparing myself, when you die, that is all you need,” he said. Desperado Mansoury longed for war and breaking the sound barrier chasing those sons of dogs, but the closest thing he could get to that feeling was climbing his old MiG 218040 rusting away at the October 6 Panorama. General Abu Bakr told me that he was an example of a pilot who “lost his wings”.

Abu Bakr and his generals say they won the war in 1973 – it is celebrated every year in October when he gets busy attending lectures and TV talks. Just like any of them, he knows they must pass on their mission before they are gone. And sometimes I think what propelled the generals, or the comrades and their curses or underground Islamist singers, was a belief in something greater than their frail existence. If I learned anything from my quinquennial crusade with the faithful is that it requires sacrifice, tenacity even vanity, and, if things go badly, hope.

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.